- Home

- Research

- Achieving Excellence - Research at Washington University Orthopedics

- Engineering Cartilage for Joint Preservation

Engineering Cartilage for Joint Preservation

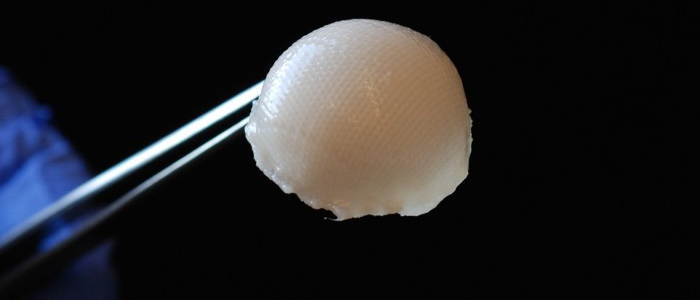

A 3-D, biodegradable, synthetic scaffold has been molded into the precise shape of a hip joint. The scaffold is covered with cartilage made from stem cells taken from fat beneath the skin.

In three to five years, cartilage grown and engineered in a lab may be available to treat arthritic hips and potentially eliminate the need for many total hip and knee replacements.

The groundbreaking laboratory research, under way at Washington University School of Medicine, already has received international attention and now is on a fast track through more studies to eventually evaluate its potential use in real patients.

Washington University biomedical engineering PhD student Ali Ross and Farshid Guilak, PhD, a professor of orthopedic surgery, show a container with a prototype of a living hip replacement. The scientists have coaxed stem cells to grow into new cartilage on a 3-D template shaped like the ball of a hip joint.

Washington University biomedical engineering PhD student Ali Ross and Farshid Guilak, PhD, a professor of orthopedic surgery, show a container with a prototype of a living hip replacement. The scientists have coaxed stem cells to grow into new cartilage on a 3-D template shaped like the ball of a hip joint.

Farshid Guilak, PhD, and his team have successfully taken adult stem cells, placed them onto a 3-D scaffolding model of a hip joint and manipulated the cells to grow into cartilage tissue. Even more exciting is that they also have genetically engineered the cartilage tissue by inserting a gene into the stem cells so that they will release anti-inflammatory drugs on cue.

“These stem cells are genetically modified with a genetic switch so that when you introduce a specific drug, the anti-inflammatory molecules turn on to fight pain and inflammation in the joint,” says Guilak. “This is an example of a highly targeted therapy because the cells produce the drug only in the joint and we can turn it on or off or tune it to the amount of anti-inflammatory medication that is needed.”

Already Guilak has translated his basic research into animal models and the early results are looking “excellent.” He hopes to gain FDA approval for physicians to start clinical trials using engineered cartilage within the next several years. “I envision that physicians can take a patient’s own stem cells out of a layer of subcutaneous fat and send a sample off to grow new cartilage that can be re-implanted back into the patient.”

The potential impact of his team’s discovery is huge. More than one million total joint replacements are performed annually in the United States. Because current artificial joints are made of metal and deteriorate over time, the average lifespan of a total joint replacement is said to be around 20 years, making the procedure more problematic for young or middle-aged patients, who might then be subjected to a riskier second joint replacement procedure later in life.

“Revision joint replacements bring with them a higher risk of infections and implant failure,” says Guilak. “So if we can preserve a person’s own joint by inserting new cartilage tissue to protect the bones from deterioration, then we might be able to offset the need for a total joint replacement over a long term.”

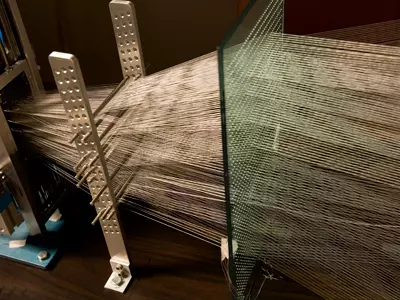

Guilak, an orthopedic researcher with a background in biomedical engineering , is co-director of Washington University’s Center of Regenerative Medicine and holds dual appointments in the department of developmental biology and biomedical engineering. He’s taken his research and formed an emerging bio-tech company called Cytex Therapeutics, which developed a type of weaving loom technology to create the specialized scaffolding for stem cells to grow on.

“We basically weave together hundreds of biocompatible fibers and then manipulate it into the exact shape of a joint,” he explains. “Creating the fabric is not a limitation, as we can readily scale up the manufacturing process to make large amounts of the material. The harder and longer process is when we isolate the stem cells and get them to grow in the right shape of a patient’s hip and in the right density for cartilage tissue.”

Guilak calls the process 3-D weaving because the stem cells are incorporated within the scaffolding. It takes approximately four weeks before the stem cells morph into cartilage tissue. The underlying scaffold then slowly disintegrates over time, leaving just the cartilage tissue.

“We’re focusing on the hip joint first because the shape of the knee joint is more complex,” he adds. “We think, if research continues to go well that we can also look at using this technology to treat certain types of shoulder and wrist pain.”

Once the approval is given for human clinical trials, Guilak stresses that long-term studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of bio-engineered cartilage replacements. An immediate advantage he sees is that because his cartilage tissue is a living tissue, it will stretch and grow with a child’s joint, making this a potential option for children with arthritis or those who have failing joints early in life. “Metal joint replacements don’t grow or change in size,” he explains. “This makes our research a potential game-changer for young patients and I’m looking forward to advancing our laboratory investigations to make a difference in actual patients.”

Hear this story on St. Louis Public Radio.

Next article: Understanding Low Back Pain