- Home

- Research

- Achieving Excellence - Research at Washington University Orthopedics

- Biological Research

Biological Research

A fundamental shift is under way now in the field of orthopedic research. “The ways to treat musculoskeletal disorders are slowly switching from surgical and mechanical approaches to more biological approaches,” says Matthew Silva, PhD, the Julia and Walter R. Peterson Orthopedic Research Professor, Vice Chair of Research in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Associate Director of the Musculoskeletal Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine.

So instead of taking out damaged tissue and replacing it with synthetic materials, such as with joint replacement, scientists are now working to preserve, enhance and restore original bone and joints to make them better.

“We are focused on ways that turn certain cells ‘on’ or that produce new cells to heal or regenerate a person’s own tissue,” says Silva.

Matthew Silva, PhD, in his research lab at the BJC Institute of Health building on the Washington University School of Medicine Campus.

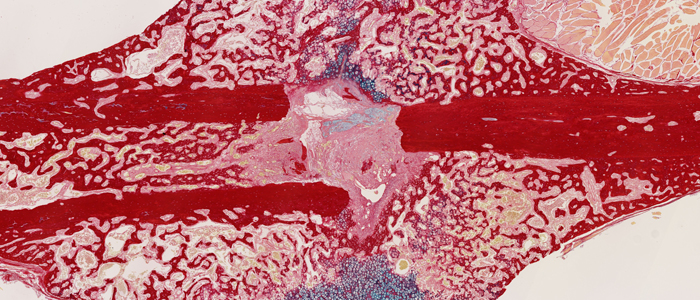

In his research lab, Silva, who has a background in mechanical engineering, is investigating how controlled loading on bones can trigger new bone growth and increased bone mass. His work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health for more than 15 years, primarily because what he finds in his basic research efforts could point to better ways to treat osteoporosis and bone fractures. Osteoporosis impacts more than 10 million older adults in the United States and studies estimate that more than 43 million older adults have low bone mass, a precursor to osteoporosis.

“In your skeleton, there are cells that build bone, called osteoblasts, and cells the break down and resorb bone, called osteoclasts,” he explains. “What happens in looking for new ways to treat osteoporosis is that some of the drugs used today have a number of limitations. While they may block osteoclasts from breaking down bone, they also seem to cause osteoblasts to shut off. Our goal is to figure out how to de-couple these two effects and come up with new strategies that increase bone mass.”

Already, Silva and his team have found that increased mechanical loads stimulate bone formation regardless of age, which could be good news to older adults if they start weight-bearing exercise programs. His team also has identified that loading turns on specific molecules called Wnt ligands that have been found to be powerful regulators of bone formation. These proteins activate molecular signaling pathways that are responsible for bone formation, and mechanical forces are a way to turn on their activity.

“We now are trying to find out what triggers Wnt ligands and activates the molecular signaling pathways that are responsible for bone formation,” says Silva. “While we are conducting basic research in the lab, these efforts are all about trying

to understand the biology of different tissues so that we can design the next generation of treatments.”

These biological approaches are being investigated on multiple fronts at Washington University School of Medicine. From coaxing stem cells to producing living hip cartilage in a lab to using nanoparticles with anti-inflammatory molecules attached to reduce inflammation in arthritis laboratory models, these leading edge research efforts could soon translate into better clinical care for patients diagnosed with bone fractures, osteoarthritis or osteoporosis.

“We are focused on parts of the musculoskeletal system that have the most disease prevalence,” Silva notes. “As we identify potential breakthroughs in the lab, we are hiring more translational researchers to push that knowledge into clinical trials, which then could positively change clinical practice guidelines.”

“The reality,” he adds, “is that in order to have successful new interventions, we need to better understand the biology of the musculoskeletal system and identify strategies that will allow us to manipulate those biologic triggers to come up with new treatments.”

Next article: Engineering Cartilage