- Home

- Research

- Achieving Excellence - Research at Washington University Orthopedics

- Juvenile Inflammatory Arthritis

Juvenile Inflammatory Arthritis

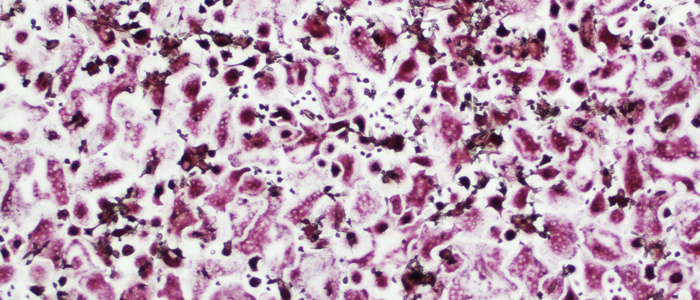

Image representing human osteoclasts (red cells) derived from circulating monocytes and grown in the presence of plasma from sJIA patients.

Roberta Faccio, PhD, clearly remembers the “a-ha” moment when she realized that a previously unknown gene impacted the development of osteoclasts, cells that are responsible for breaking down and resorbing bone.

“We were researching how a specific cell signaling pathway called the Phospholipase C gamma 2 (PLCγ2) pathway controls the activation of osteoclasts and their precursors, the macrophages, which are immune cells involved in inflammatory diseases such as arthritis,” says Faccio. “By using a gene array to compare macrophages from mice expressing PLCgamma2 and mice lacking this molecule, we found a gene, Tmem178, differentially expressed between the two groups that turned out to be a negative regulator of osteoclast formation.”

In other words, Faccio and her team found that when Tmem178 was not present in osteoclast precursors, the number of osteoclasts increased, which then led to decreased bone mass and the development of osteopenia, a condition commonly observed in postmenopausal women and in patients with inflammatory arthritis.

Roberta Faccio, PhD, in her laboratory at the BJC Institute for Health Building on the Washington University School of Medicine campus.

Roberta Faccio, PhD, in her laboratory at the BJC Institute for Health Building on the Washington University School of Medicine campus.

In her research lab, Faccio seeks to understand the connections between bone and the immune system with the goal of identifying new therapeutic targets for inflammatory arthritis. While she and her team identified Tmem178 through basic research efforts, she broadened her studies to ask if this gene could also be implicated in bone loss in patients with inflammatory arthritis. “We looked at diseases driven by macrophages and osteoclast activation and decided to focus on juvenile inflammatory arthritis,” Faccio says.

Nearly 300,000 children in the United States have arthritic diseases and the most common type is juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Among the different subtypes, systemic JIA is particularly problematic because it affects not only the joints but also other parts of the body, including the liver, lungs, and heart. While the causes of sJIA are unknown, it is recognized that the body’s immune system attacks healthy cells and tissues. Furthermore, differentiation of macrophages into bone resorbing osteoclasts was responsible for persistent erosive arthritis in up to 50% of sJIA patients prior to treatment with biologic agents (such as IL1 or IL6 inhibitors), but remains an issue for a significant subset of patients (CARRAnet registry data). “Current therapies are aimed at either reducing inflammation or blocking the osteoclasts,” says Faccio. “My goal is to find a common mediator to target both.”

Working with colleagues at Stanford University, Faccio tested Tmem178 levels in human monocytes (inflammatory cells in the blood that can become macrophages or osteoclasts when grown in certain conditions) exposed to plasma from children with sJIA. She found that Tmem178 levels were significantly reduced when compared to healthy controls. Just like her initial laboratory research, she found that when levels of Tmem178 decreased, the monocytes were differentiating into osteoclasts faster and were better at resorbing bone. What was even more striking was that plasma from sJIA patients with erosive disease was more potent at inducing osteoclast differentiation than plasma from patients with less severe disease.

“We are still studying what’s making the Tmem levels go down, but we think Tmem178 could be a biomarker that will tell us which patients may develop a more severe and errosive disease later in life,” she says. “We also find that when Tmem178 levels go down, the monocyte express higher amounts of inflammatory cytokines.”

That’s important because up to 10 percent of juvenile arthritis patients develop a severe and deadly form of the disease called Macrophage Activation Syndrome, characterized by prolonged spikes in inflammation and multi-organ dysfunctions. Says Faccio, “We are currently working on understanding whether loss of Tmem178 could affect the development of this complication.”

“I want to know how Tmem178 is regulated in patients and how levels are reduced in inflammatory conditions,” Faccio says. “If we understand how it works, we can, perhaps, find ways to modulate it.”

She adds, “In my research, I’m not so much an orthopedic researcher, but an osteo-immunology researcher. I’m bridging the gap between the fields of orthopedics and immunology.”

Next article: Biological Research